In a first-ever near-infrared study of a recurrent nova beyond the Milky Way, astronomers have discovered exceptionally high temperatures and unexpected chemical signatures, pointing to an especially intense explosion.

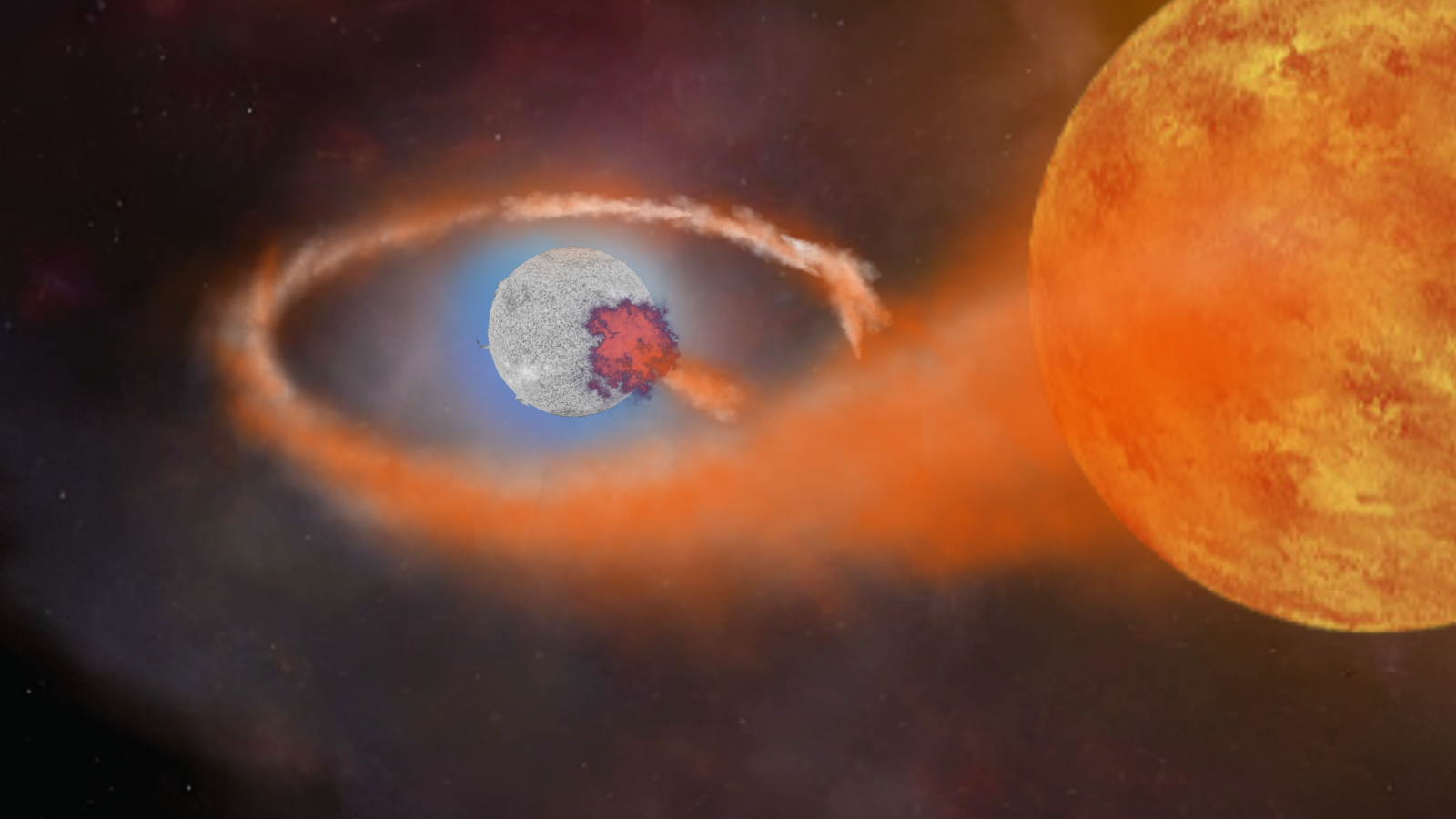

Nova explosions occur in semi-detached binary systems containing a cool late-type star and a white dwarf.

“A hot white dwarf star, about the size of the Earth but having mass comparable with that of the sun, siphons off material from its cool companion star,” explained Nye Evans of Keele University to Space.com. “The material from the cool star piles up on the white dwarf’s surface and eventually detonates in a thermonuclear runaway. This is a nova explosion.”

Most novas have been seen erupting once, but a rare few have been observed to explode multiple times. These are known as recurrent novas, with intervals between eruptions ranging from just a year to several decades.

“Once the explosion has subsided, the siphoning starts all over, and in time another thermonuclear explosion occurs, and so on, and so on,” explained Evans.

Fewer than a dozen recurrent novas have been identified in our galaxy — more are known beyond the Milky Way, most of them in the Andromeda Galaxy (M31), with four in the Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC).

Nova LMCN 1968-12A (LMC68), which is located in the LMC, was observed for the first time in 1968. In 1990, it was observed in eruption again, which made it the first extragalactic recurrent nova ever observed, with eruptions occurring like clockwork every four years.

“In systems like LMC68, less mass is ejected in the nova explosion than is gained by transferring from the cool star,” said Evans. “This means that the mass of the white dwarf is steadily increasing. In time, it will approach a critical value … above which the white dwarf cannot support its own weight, and it will implode, one outcome of which is a supernova explosion.”

After its 2020 eruption, NASA’s Neil Gehrels Swift Observatory had been closely monitoring LMC68 for months, anticipating its next eruption, which occurred in August 2024.

“LMCN 1968-12a is about 50 times further away than nova explosions in our own Milky Way galaxy, and hence about 2,500 times fainter,” said Evans. “You have to use the largest telescopes in existence [to see it, and] you need to get to them as soon as they explode; you therefore disrupt other observing programs.

“There’s a lot of good will involved as there aren’t many large infrared telescopes.”

Nova LMCN 1968-12A (LMC68), which is located in the LMC, was observed for the first time in 1968. In 1990 it was observed in eruption again, which made it the first extragalactic recurrent nova ever observed.

Analyzing the chemical make-up of a unique nova

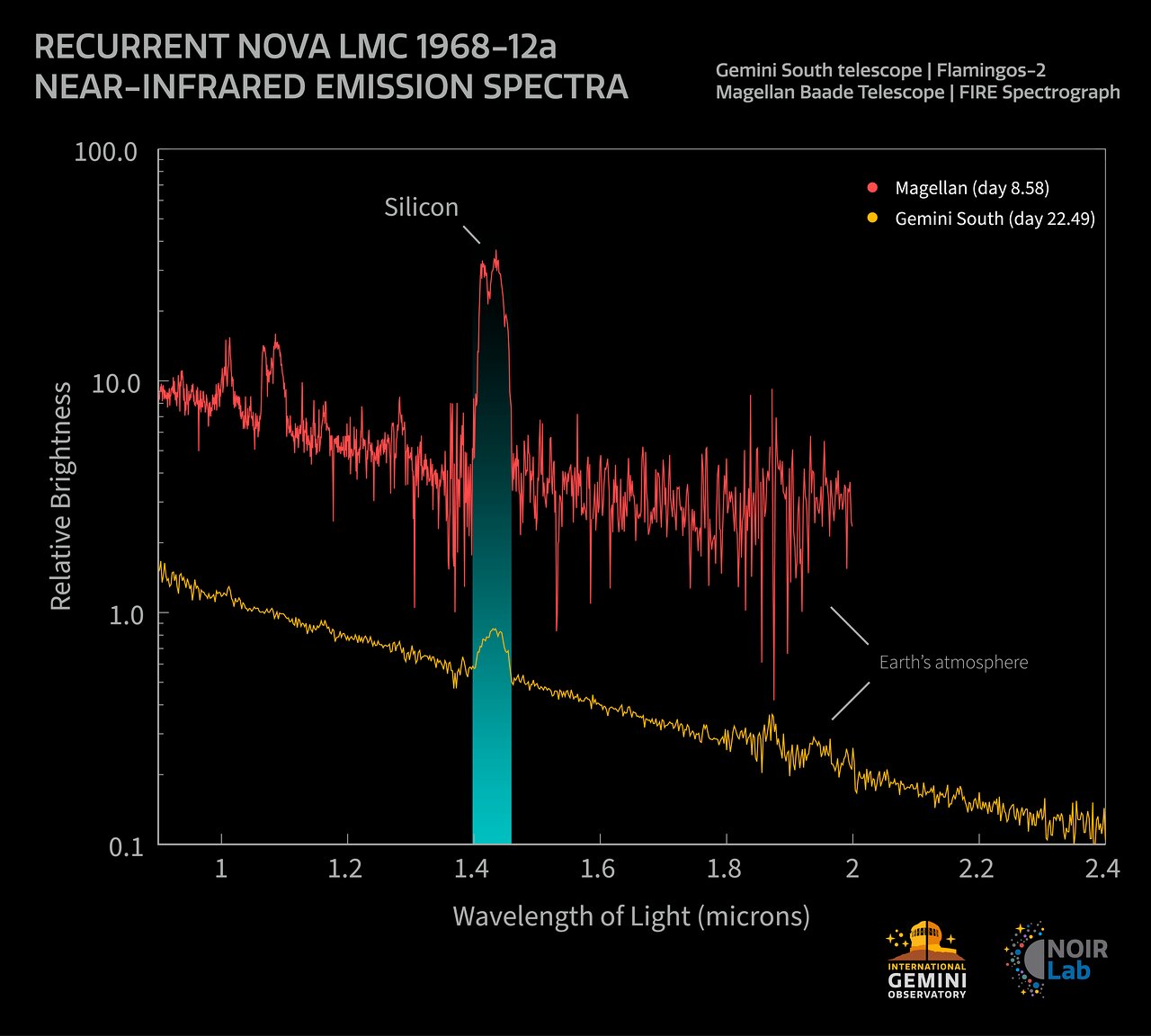

By capturing LMC68’s near-infrared light for the first time, the team of astronomers was able to study its ultra-hot phase, when many elements become highly energized. This provided valuable insights into the extreme forces driving the nova’s eruption.

They did this using spectroscopy, a technique for analyzing the different wavelengths of light absorbed and emitted during the eruption.

This allows them to identify the chemical elements present and understand how they are affected by the nova’s intense heat, which typically “ionizes” or excites the atoms, causing their electrons to jump to higher energy levels before returning to their original state.

“Emission lines are formed when an atom or ion relaxes from a high energy state to a lower energy state,” explained Evans. “The energy difference is emitted as a photon of infrared light that is a unique signature of the atom or ion. This is how we know what the stars are made of.”

“While other near-infrared studies of similar novas in the Milky Way typically revealed signatures from various elements known as “metals” (which, to astronomers, is any element other than hydrogen or helium, though a chemist might have something to say about that), the team was surprised to find that LMC68’s spectra contained an exceptionally bright signal from silicon atoms that had been ionized nine-times —a process that demands an immense amount of energy.

“The ionized silicon shining at almost 100 times brighter than the sun is unprecedented,” Tom Geballe, NOIRLab emeritus astronomer and co-author of the paper, said in a statement. “And while this signal is shocking, it’s also shocking what’s not there.

“We would’ve expected to also see signatures of highly energized sulfur, phosphorus, calcium, and aluminum.”

The team argues that it might be possible that a high concentration of electrons in the nova’s outer region could have caused excited atoms to lose energy through collisions rather than emitting light. But while this is a possibility, it doesn’t explain why the usual spectral lines that are typically seen in the light of recurrent novas are completely absent in this case.

This suggests that something unusual is happening with LMC68 that’s different from typical novas.

LMC68 differs from galactic recurrent novas because its companion star likely has lower metallicity, meaning a lower quantity of heavier elements, which is typical of the LMC. Low-metallicity stars can lead to more powerful nova explosions, as more material is needed to trigger the eruption.

While the secondary star’s metal deficiency could influence the nova’s composition, it doesn’t fully explain the absence of metal lines in the near-infrared. The explosion still processes material through the usual thermonuclear runaway, but the expected metal signatures are missing.

The higher coronal temperature of 5.4 million degrees Fahrenheit (3 million degrees Celsius) in LMC68 might offer a clue. The high temperature of the coronal gas could lead to a process called collisional ionization, in which atoms in the gas become more ionized than usual, meaning they lose more electrons and reach higher energy states.

“To strip the atom or ion of so many electrons requires the input of energy,” said Evans. “In collisional ionization, the energy is provided by fast electrons that collide with the atom/ion, imparting their energy to it.”

This means that the ions that are typically seen in the coronal phase of other novas are less abundant in their “normal” forms because they have been pushed into these higher states.

The fact that the gas around LMC68 is metal-deficient also means it contains fewer elements like magnesium and calcium compared to typical stars. When this gas goes through the thermonuclear runaway process (the explosion in the nova), the lack of these elements is amplified, leading to a lower abundance in the explosion’s remnants.

This combination — of high temperatures and metal deficiency — could explain why metal lines were absent in current observations.

“With only a small number of recurrent novas detected within our own galaxy, understanding of these objects has progressed episodically,” said Martin Still, NSF program director for the International Gemini Observatory. “By broadening our range to other galaxies using the largest astronomical telescopes available, like Gemini South, astronomers will increase the rate of progress and critically measure the behavior of these objects in different chemical environments.”

While an intriguing theory, the team emphasizes the need for modeling studies to more accurately measure the products of these reactions and more observations using longer wavelengths of light to confirm the hypothesis.

The team’s research was published in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.