Wildfires in the western U.S. are larger and more frequent now than in the past. And the number of homes, businesses and other structures lost to the flames has skyrocketed.

This is because such blazes are now much more likely to turn into urban firestorms—such as those that recently tore through the Los Angeles area, suburbs of Denver and the town of Lahaina, Hawaii. These catastrophes are increasing as communities expand into wildfire-prone areas—and as climate change increases the likelihood and frequency of the conditions that fuel such conflagrations.

Wildland management techniques, such as thinning out undergrowth, are important to reducing fire risk but will not solve the problem on their own, fire experts say. Likewise, “assuming a firefighter can protect our home is no longer a safe or responsible expectation to have,” says Kimiko Barrett, a wildfire resilience researcher at Headwaters Economics, an independent, nonpartisan research group. In the recent case of Los Angeles, “even the best-equipped, best-trained, best-staffed” firefighting force in the country “could not stop what happened once it got into the structures,” says Steve Kerber, vice president and executive director of the Fire Safety Research Institute (FSRI).

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

People have to completely reset the way they think about dealing with fire danger, these and other experts say, by making homes more resistant to fire. “The big social, cultural paradigm shift that is needed is in us understanding, as a society, that wildfires are inevitable, that the risks are increasing and that we need to learn to live with these increasing risks,” Barrett says. Risk mitigation involves what some experts call “hardening” homes to make them less susceptible to fires and to prevent flames from getting that first toehold in an urban or suburban area.

And it’s not only an issue out West. Places from the New Jersey Pine Barrens to the Appalachian Mountains are at risk of wildfires that can spill over into residential firestorms.

There are several certification programs and homeowner guides that communities can turn to in order to become more fire-resistant, from voluntary programs that individuals can carry out, which are run by organizations such as the nonprofit Insurance Institute for Business and Home Safety (IBHS), to formal building code programs that can be enacted at the state or local level. Regardless of the resource, all recommendations for the best materials and tactics for fire resistance are grounded in the same research, which uses observations from real fires, controlled tests in labs and computer simulations. “We’re all saying the same science,” says IBHS chief engineer Anne Cope, and “the science is very clear.”

How do houses catch fire?

A wildfire can threaten a house in three main ways: it can produce embers, make direct flame contact and emit radiant heat.

“The number one concern is embers,” says Karl Fippinger, vice president of fire and disaster mitigation with the International Code Council, a nonprofit that develops model building codes. These “tiny little balls of fire,” as Barrett calls them, can travel several miles ahead of a fire front. If they collect in the corner of an eave or on landscaping plants, or if they slip through cracks into the house, “all of these flammable surface areas are vulnerable to ignition,” Barrett says. If a home ignites from embers, there’s a 90 percent chance that it will be completely lost.

Direct flame contact with a structure is an obvious danger, and objects that surround a house can put it at greater risk. The more flammable objects there are in the yard or other space around a house, the more likely the flames are to spread to the house itself.

Homes can also catch fire from radiant heat, typically from another building next door. If that radiant heat is hot enough, it can cause vegetation next to a building to combust and can even shatter windows—allowing embers inside. And the radiant heat from a house fire is tremendous. “There’s a reason why you cannot hold your hand over a candle,” Cope says, and “a candle is pretty small.” When a home catches fire, there is “a lot of material that’s not only flammable, but it’s also often manufactured with petroleum,” Barrett says. “So when it burns, it’s going to burn really, really hot for a really long time.”

What does “wildfire-resistant” mean?

This concept can go by a number of terms—”wildfire-resistant,” “wildfire-prepared,” “hardened”—but it does not mean “wildfire-proof.” To achieve that, you’d need what effectively amounts to a concrete bunker—not exactly something that suggests “home sweet home.”

Instead the practical aim is to make a house less susceptible to the three main fire threats, which buys time both for people to evacuate and for firefighters to arrive. The longer it takes for a house to start burning, the better the odds that firefighters can get there and stop the flames, Fippinger says. Stopping them before they find purchase in the built environment is critical: Once a single house catches fire, “it is then propagating the spread of the fire into the neighborhood,” Barrett says, “and that’s very distinctive with wildfires, in contrast to other hazards. You do not see that with floods; you do not see that with hurricanes.”

Some of the design elements that experts recommend can be retrofitted into an existing house quite cheaply and easily. But retrofitting other elements can be much more expensive. When building new, though, “it’s almost the exact same cost” as using more standard materials and techniques, Cope says. Many of the recommendations also improve energy efficiency or provide protection from high winds as well.

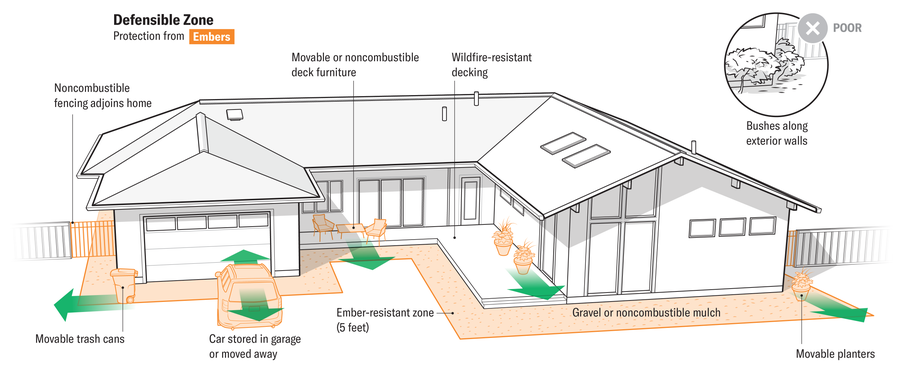

What is “defensible space”?

One of the first, and often easiest, places to start when hardening a home to wildfire is what experts call “defensible space.” This is a bit like a home’s personal space. Essentially, you want to reduce or eliminate any combustible material within five feet of the house to reduce the risk from embers and within 100 feet to protect against active flames and radiant heat. An individual home’s defensible space can overlap with neighboring homes or other structures, especially in densely populated areas, so one homeowner’s choices in this regard can affect the risk for neighbors as well.

Within the defensible space, it’s important to consider the flammability of plants, landscaping materials (such as mulch or pine straw), fencing, vehicles, trash cans, sheds or other outbuildings, decks and outdoor furniture.

If a home has a wooden fence, any section that touches the house should be made from metal or some other noncombustible material. Outbuildings can be kept a certain distance from the house or constructed from noncombustible material, or both, as can decks and patios. On “red flag” days (when the wildfire threat is high), furniture, garbage cans and other movable objects can be brought inside—just as people do in areas prone to hurricanes or tornadoes. And though a healthy green bush doesn’t seem like it’s primed to burn, in an urban conflagration, “all those beautiful bushes are little green gas cans,” Cope says. So planting flowers instead of larger plants near a home might be a safer bet.

These recommendations don’t mean a house can’t still have curb appeal. Plants can be put in movable containers, and there are noncombustible materials that mimic the look of wood and can be used for fences and decking.

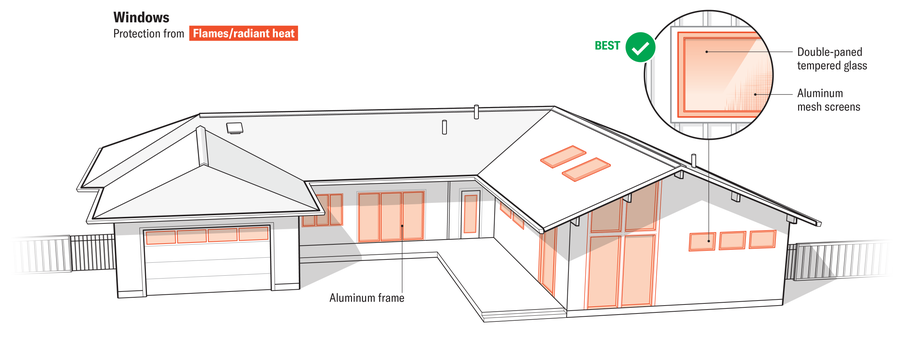

What are the most fire-resistant types of windows?

Kerber and his colleagues in the FSRI lab have done thousands of experiments on windows of different thickness, material and frame type. They start with just the glass, then work their way up to scale models of the exterior walls of houses to see how well those walls hold up to a nearby fire.

Their work shows that the ideal windows for resisting the heat from fires are dual-paned and made with tempered glass. The frame should be made from aluminum or other noncombustible material, not wood.

Many houses across the country already have dual-paned windows for energy efficiency, and their insulative properties also help with fire safety. “The same thing that works for energy efficiency, to keep the energy in your house, works to keep the energy out” in a fire, Kerber says. And if the outer pane does crack, the inner pane keeps it in place so that the whole window doesn’t shatter and let in embers or flames.

Additionally, tempering makes the glass stronger; think of the tempered glass cookware that goes into ovens.

There are also shutters made to protect windows from fire that are akin to the storm shutters or plywood sheets that people sometimes put up ahead of a hurricane. Kerber’s team is now conducting experiments to see which types offer the best protection.

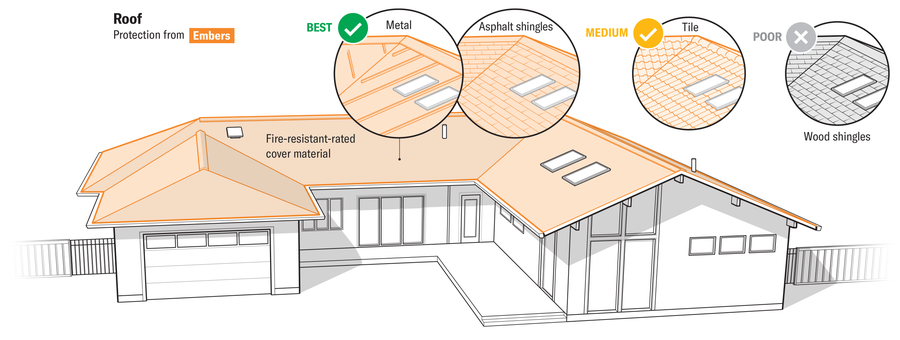

What kind of roof is most fire-resistant?

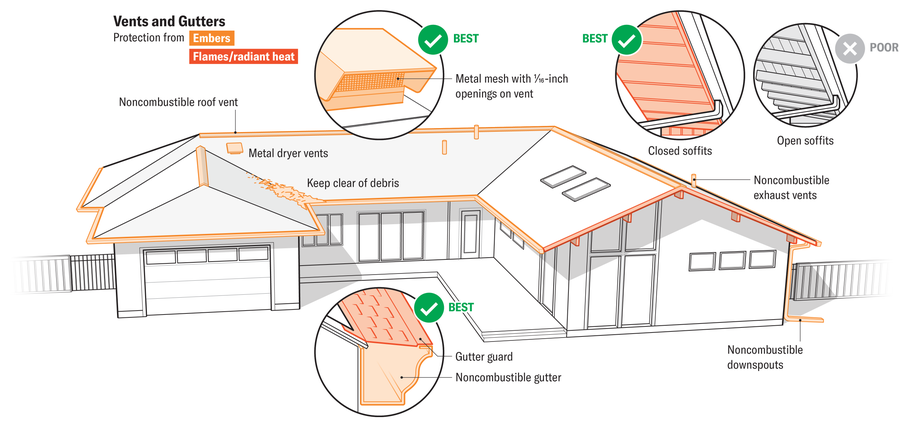

A range of factors affect the relative risk of a roof catching fire. The safest roofs have simple shapes—few or no dormers (protruding structures, usually with windows) or other architectural features where debris or embers can collect—and are made from noncombustible materials, such as asphalt or metal. Tile roofs are popular in some areas, and though they are noncombustible, they can crack naturally or from various stresses, creating crannies that can trap flammable debris or flying embers. Debris such as leaves should be regularly cleared from roofs and gutters, and the latter can be covered for further protection.

Unvented attics are safest from embers, but attics in some climates need to be vented to manage airflow and moisture and to avoid damage to the home. If a home has attic vents, they should be covered with nonplastic screens or replaced with nonplastic vents that meet certain specifications for keeping out embers. These are often easy and cheap for homeowners to install themselves, Cope notes.

Eave overhangs and open eaves provide more surface for flames or embers; they should be enclosed. Enclosing eaves can be relatively inexpensive.

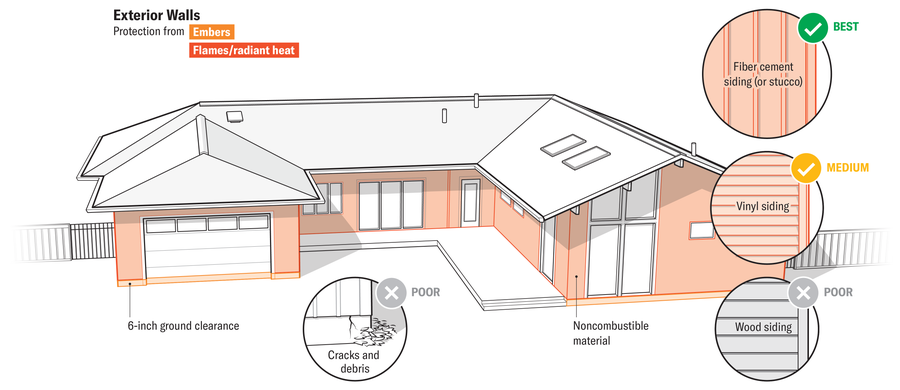

What walls are the most fire-resistant?

Ideally, exterior walls should use noncombustible fiber cement or stucco materials instead of vinyl siding or wood. “They’ve now made very decorative cement and stucco options that are easy to install, that aren’t super expensive,” Kerber says.

If fully replacing the siding on an existing house isn’t feasible for cost reasons, the most important place to target is the bottom six inches of wall—this helps prevent ignition from piles of embers that can accumulate there. That six-inch noncombustible zone should also be applied to doors, floor-to-ceiling windows or any other feature in that space.

Gaps or cracks larger than one eighth of an inch in width should be caulked or plugged to prevent embers from entering them, smoldering and starting a spot fire.

Why is it important for whole communities to harden their homes?

For a home to be fully wildfire-resistant, every part of it needs to be up to standards. You can’t do 20 percent of the recommendations and be 20 percent safer from wildfires. “It doesn’t work that way,” Kerber says. But homeowners have to start somewhere, and Cope suggests making a plan and tackling one piece at a time if a full upgrade isn’t in the cards.

And even if one home meets wildfire-resistance standards, it’s not out of the proverbial woods. “One poorly placed shed that’s unprotected could take out an entire community,” Kerber says.

That means that changes need to happen at the community level. “Whether you want it to be a group assignment or not, it is,” Cope says. Some jurisdictions have passed wildfire-resistant building codes—but in California, for example, they only apply to homes built after 2008. There are also regulations on creating ample defensible space in some wildfire-prone areas, but those haven’t yet been fully enforced, Cope says.

“It requires change,” she says, and “change is difficult.” But it can be done. As Kerber points out, parts of Florida that were wiped out by hurricanes have built back, adhering to stronger codes—and survived the next storm as a result. Hardening homes to deal with wildfires is ultimately “how we get out of paying billions of dollars in damage” with repeated catastrophes, Kerber says.

Public guides from the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (Cal Fire) and IBHS have more details on the specifications for wildfire-resistant homes.”